To Resist the Infantilization of Torah

(Technical note: Gmail users may have these emails going to the – “Promotions” tab. Be sure to move it to your regular inbox to ensure it doesn’t get lost.)

I never began this email series with any rules in mind, but I’d argue that I’ve been unintentionally adhering to a simple and uncontroversial principle in sharing pre-Pesaḥ ideas: only share the ideas of others that I think are good.

But not today.

Because, while reading an otherwise fantastic Haggadah, I came across what was, for me, a blood-boiling idea. And while it wasn’t original to the commentary I was reading, I won’t cite either the rabbi who originated the comment nor the author of the Haggadah I was reading – given that I’m about to criticize the message for being responsible for one of Judaism’s major problems these days.

But the message was thus. We begin the section of the Four Sons by declaring keneged arba‘a banim dibberah Torah, that “the Torah is keneged to four types of sons.” What does this word keneged mean? To answer, the commentator shared the view of a prominent rabbi of the recent past.

In contrast to other fields of knowledge – in which the materials learned by a first grader are fundamentally different to the materials learned by the experts in the field – when it comes to Torah, the comment of Rashi read by a grade schooler is the very same comment read by the greatest rabbis.

As the commentary puts it, summarizing: “The Torah is for everyone! No matter how elementary or advanced one is, it is the same exact text that is being studied.”

You may wonder what, exactly, angers me so much about this idea – especially when it is factually correct. Great rabbis and small children alike do learn the same comments of Rashi, while Elementary School students are not known for reading the same journals as academics (or maybe that’s complaint #20,836 about Jewish Day Schools: the children are not introduced early enough to the New England Journal of Medicine).

But what upsets me about this idea is how much I think it misses the point. That everyone is reading the same material, the same comment of Rashi, says nothing about the quality of intellectual endeavor. It papers over the depth a serious adult can extract from Rashi (perhaps by doing something I cannot, and get through what I find to be one of the most boring books ever written on a fascinating topic); it makes no distinction between a child’s approach and that of an adult.

And herein lies the problem across large swaths of the Orthodox world: we accept the infantilization of the Torah. We assume that because the Rashi read by great rabbis is the same Rashi read by children it must be aimed at a child’s intellect.

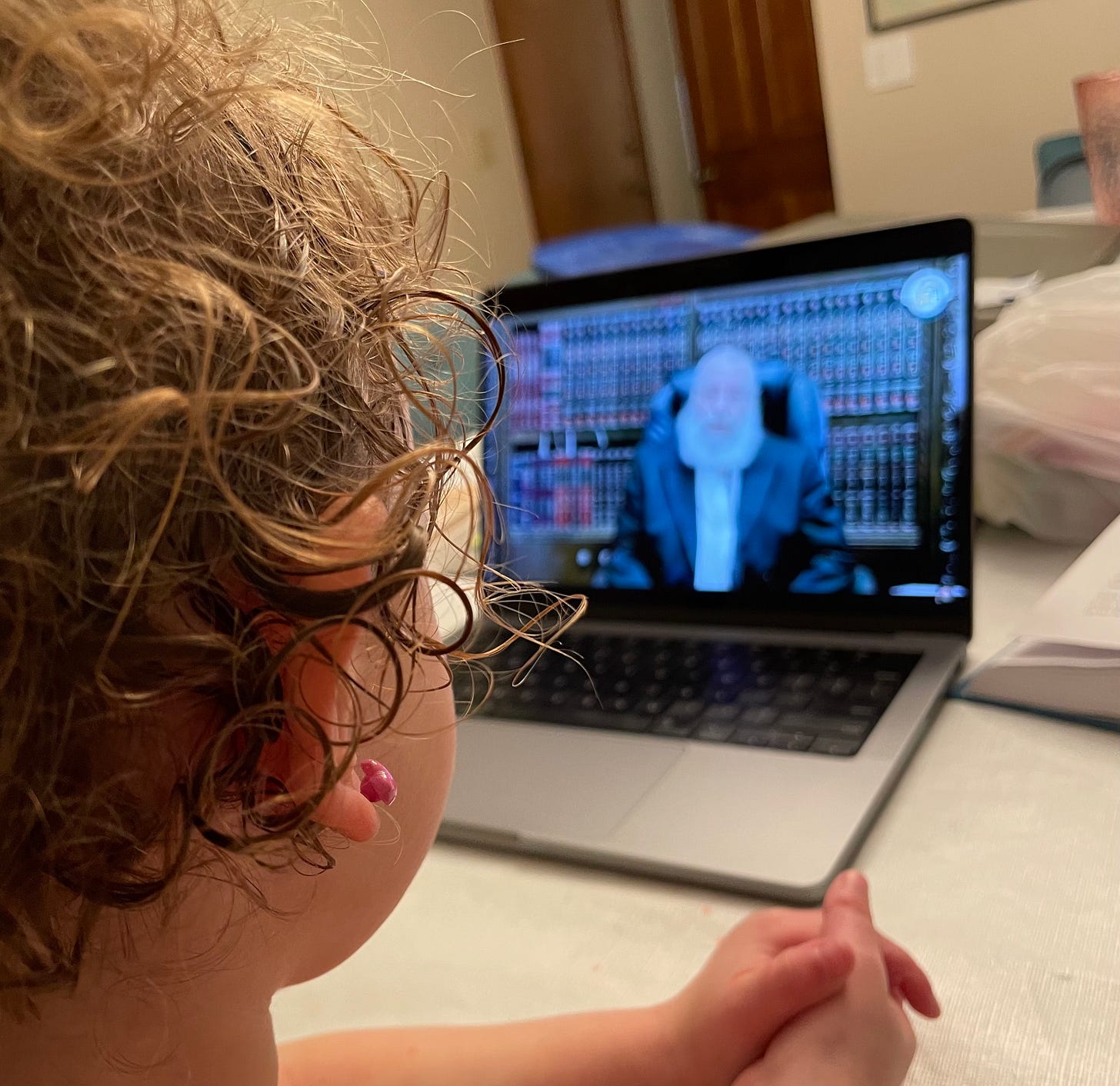

And so, we dismiss Rashi as a commentary unworthy of our own intellects or, even worse, we embrace a Judaism that makes no intellectual demands of us. We delight in Jewish story time and cute ideas, yet shy away from anything that demands our cognitive effort. (Or, as my rebbi, Rabbi Jeremy Wieder put it recently, we just want to be entertained.)

Rabbis, it should be stressed, are as guilty of this as anyone. There’s a well-known principle in the rabbinate that you must begin every derasha with a story or joke because the audience doesn’t actually care to learn. (Admittedly, I’m happy to share stories about soccer or Pokémon from the pulpit but that’s because I think you should care about these things, too.)

But this cannot be the meaning of keneged arba‘a banim. We must resist this definition.

Instead, I’d like to argue that keneged here means what a teacher these days would term “differentiated learning.” The Torah speaks differently to four different sons, even as it uses the same topic and material. And we must view the Four Sons as a case study. The wise son is encouraged to dive into the depths of Pesaḥ’s laws. The wicked son is taught harsh mussar rooted in the Pesaḥ story. Only the simple son is taught a nice idea about Pesaḥ, while the son who does not know how to ask is fed the basics of the holiday. Sure, they’re all learning about Pesaḥ, but each to their own level.

And if we strive to be ḥakhamim, wise, we must embrace the challenge and difficulty of Torah learning. We must learn the esoteric, arcane, and complex aspects of our religion – even when it’s far less enjoyable and entertaining than a delightful story or Haggadah.