I had an idea for a shiur series – alliteratively and delightfully entitled Qontroversial Questions on the Parashah – that, over the next few weeks, I hope to experiment with as a written, email-only shiur. Subscribe to continue to receive these and please share with those you think would be interested.

I.

Last month, I came across a gemara that has been lurking in the back of my mind ever since. In a wider discussion about wayward children, the gemara notes the perception of one of the sons of Yosef b. Yo‘ezer (Bava Batra 133b). To cut a long story short, Yosef b. Yoezer’s son, though no longer religious, found himself brokering a deal with the Beit ha-Mikdash.

Despite being owed thirteen vessel’s worth of money by the Beit ha-Mikdash for a pearl he had found, the Beit ha-Mikdash only had seven to give him. Seemingly out of an abundance of good will, Yosef b. Yoezer’s son agreed to split the difference: he took the seven vessel’s worth of money and consecrated the remaining six vessel’s worth as a gift to the Temple.

And though this sounds like an objectively positive act, the gemara ends the story with a debate as to the reaction: there are those who say that he donated six vessel’s worth of money to the Temple, yet there are those who say that he deprived the Temple of seven.

And the reason this story has been so constantly on the back of my mind is because it’s a perfect illustration of how our beliefs about a person – whether we deem them good or bad to begin with – inform how we view their subsequent actions. Yosef b. Yo‘ezer’s son wasn’t religious anymore, and so there are those who were inclined to view him negatively. And so, even when he donated literal boatloads of money to the Beit ha-Mikdash, there were those who complained.

And while there’s lots to say about how this mentality infects our current societal discourse, I’d rather focus on a different issue: it’s a mentality that also forces us to read the Torah’s narratives in very bizarre ways.

II.

A couple of weeks ago on Parashat Toldot, I was asked a really interesting question. But my answer opened a Pandora’s Box.

The question concerned the central tension of Toldot: is it Yaakov or Esav who deserves to inherit the covenant of Avraham and Yitzḥak? The questioner contrasted this with a similar tension in Lekh Lekha and Vayera: is it Yitzḥak or Yishmael who deserves to inherit the covenant of Avraham?

Because, when it comes to the Yitzḥak/Yishmael debate, God Himself explicitly weighs in, telling Avraham directly that Yishmael is to be rejected from the covenant:

As for Ishmael, I have heeded you. I hereby bless him. I will make him fertile and exceedingly numerous. He shall be the father of twelve chieftains, and I will make of him a great nation. But I will maintain My covenant with Yitzḥak, whom Sarah shall bear to you at this season next year (Gen. 17:20–21).

But, asked the questioner, surely it would have been helpful for God to do the same thing to Yitzḥak, and explicitly inform him to reject Esav – especially considering just how beloved Esav was to Yitzḥak (Gen. 25:28).

But what made the question so strong was the recognition that God does tell Rivkah to reject Esav, but far more circuitously than He does with Avraham. After all, Toldot begins by telling us that Rivkah, disturbed by the conflict within her womb, “went to inquire of God” (Gen. 25:22). Here, God explains to her that she is carrying twins, “one shall be mightier than the other,” vĕ-rav ya‘avod tza‘ir, “and the older shall serve the younger” (v. 23).

The intent, the questioner pointed out, is clearly for Yaakov to be chosen over Esav – so why doesn’t God just say this outright? Why, instead, must God reveal it to Rivkah so cryptically, to the point that an undercurrent to the rest of the narrative is that Yitzḥak and Rivkah are battling one another over which son will be anointed the covenantal successor?

My answer (which made me regret not having a beard, because it was the perfect moment for some wise rabbinic beard-stroking) was to point out that the phrase Rivkah hears – vĕ-rav ya‘avod tza‘ir – does not necessarily mean “and the older shall serve the younger;” it might actually mean the complete opposite.

III.

I first came across this idea in Lord Sacks’[1] fantastic 2015 book on religious extremism, Not In God’s Name, which I would characterize as one of Lord Sacks’ most explicitly “Jewish” books, because he devotes a good chunk of it to reinterpreting well-known Biblical narratives in interesting ways – in other words, there’s a good number of shiurim (or email newsletters) that can be gleaned from this book.

Amidst a wider analysis of the dynamic between Yaakov and Esav, Lord Sacks points out the fundamental issue with translating the phrase vĕ-rav ya‘avod tza‘ir. Quoting the great Biblical commentator and grammarian, the late-12th- and early-13th-century French Rabbi David Kimḥi, the phrase vĕ-rav ya‘avod tza‘ir is lacking a crucial word to unlock its meaning.

Usually, a verse will use the word ’et to signal the object of the verse – that is, about whom the verse is speaking about. In other words, had Rivkah been told vĕ-rav ya‘avod et ha-tza‘ir, that would unambiguously mean “and the older shall serve the younger.” But that’s not what the Torah says. It simply says vĕ-rav ya‘avod tza‘ir, which is ambiguous. It could thus just as easily mean the complete opposite, “the younger shall serve the older.”

As Words of Myrrh’s resident specialist on Biblical grammar, Rabbi Dr. AJ Berkovitz explained to me, because both rav and tza‘ir are masculine singular, while ya‘avod is always third-person masculine singular, it is impossible to tell which word of the two – rav or tza‘ir – is the intent of the statement. (Yeah, I didn’t really get that either, but AJ knows his stuff.)

Lord Sacks then adds some other arguments, too – all of which is to suggest that the central tension of Toldot is never clarified by God the same way he clarifies the question of Yitzḥak or Yishmael. Instead, God provides Rivkah with a “choose your own adventure” prophecy – Rivkah and Yitzḥak must decide which son becomes the covenantal one, not God. (Indeed, this is why many commentators understand Rivkah’s “seeking of God” to not be a literal prophecy direct from God Himself but an oracle delivered by another, which is a much more cryptic and less definitive version of a prophetic message.)

IV.

And what all of this means is that, unlike Yishmael, who is explicitly rejected by God from His covenant, Esav’s covenantal potential very much exists within him. And yet here we encounter a problem – and while it may just sound like I’m invoking a currently in vogue idea, it’s actually a huge problem in how we read the Torah: we are biased readers.

And what I mean by this is simple: we, who are not only the descendants of Yaakov but also a people who have suffered at the hands of the descendants of Esav (given our traditional understanding of Esav as the father of Rome), are not particularly inclined to view Esav with any sympathy. And for this reason, we instinctively translate otherwise neutral (or even positive) descriptions of Esav in the Torah as indications of his evilness.

And so, Esav’s not simply a “skillful hunter” (Gen. 25:27) but a cunning one who entraps his father with his false piety (cf. Rashi). Nor is he simply an outdoorsy man but a good-for-nothing layabout (cf. the same Rashi). And Rashi takes it further, still quoting Ḥazal in the next verse, which tells us that Yitzḥak loves Esav because Yitzḥak enjoyed the meat Esav hunted for him – on which Rashi stresses that the Hebrew phrase ki tzayid be-fiv be translated differently, “[Esav] trapped [Yitzḥak] with his words.”

And this is not to say that Esav is a model of religious righteousness. The Torah stresses that Esav doesn’t attach any significance to the birthright of the oldest child – being the one to continue the covenant – “thus did Esav spurn the birthright” (Gen. 25:34). Similarly, Esav marries wives his parents disapprove of (Gen. 26:34–35). And yes, Esav does make a vow to kill Yaakov after Yaakov takes his blessing (Gen. 27:42). But if we were making a tier list of all the villains in the Torah ranking them based on how evil they are,[2] Esav is a far cry from figures such as Pharoah, Amalek, and Balaam.

And all of this builds to a head in this week’s parashah. Because our determination to view Esav as evil ruins our appreciation of the scene in which Yaakov and Esav reunite.

V.

Knowing that he must pass through the land of Seir, Esav’s territory, Yaakov is terrified. He knows that Esav swore to kill him all those years before (Gen. 27:43) and assumes Esav still wants his revenge.

The beginning of our parashah thus discusses Yaakov’s plan when he encounters Esav, along with a narrative that reflects Yaakov’s “character arc” in which he fights an angel (technically the Torah itself describes the mysterious figure as “a man”) and emerges victorious.

Then Yaakov sees Esav and his large retinue coming and bows repeatedly towards Esav as he approaches as a gesture of submission (v. 3). Indeed, Lord Sacks argues that this scene is the fulfilment of the other interpretation of vĕ-rav ya‘avod tza‘ir, as Yaakov submits to Esav (in fact, he quotes a midrash that sees the entire events at the beginning of Vayishalaḥ as Yaakov returning the blessing he had taken all those years earlier from Esav).

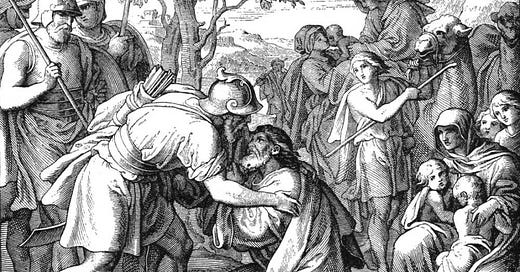

Esav’s response should be read as one of the most heart-warming and beautiful moments of reconciliation in the Torah:

Esav ran to greet him. He embraced him and, falling on his neck, he kissed him; and they wept. (Gen. 33:4)

They hug, they weep for all the years spent away – for the pain the two of them had endured being away from each other. And I think this is especially heightened by the fact that they are twins. Because, as someone married to a twin, I can authoritatively state that twins are weird – they have this super-creepy telepathic bond with one another that heightens their relationship. Yaakov and Esav aren’t just brothers distanced from one another, they’re twins.

And when Yaakov still tries to placate Esav, Esav cuts him off: “I have enough, my brother, let what you have remain yours” (v. 9). Esav then offers for Yaakov to come live with him, yet Yaakov refuses.

Yet, we don’t read this narrative the way the Torah itself describes it, because we’re still too determined to see Esav as evil and duplicitous. Thus, we say Esav still tried to kill Yaakov when they hugged, that Esav was trying to mock Yaakov and turn him towards the Dark Side by trying to encourage Yaakov to live with him. What should be such a wonderful resolution to one of the Torah’s most painful episodes – brothers divided – is transformed into a further, never-ending extension of that same pain.

*

Yet if we never went down the path of insisting Esav was pure evil from the start, we’d be able to appreciate the power of this scene. And this, I think, is something important for us to process.

Because Esav doesn’t need to be evil for Yaakov to be right. Esav doesn’t need to be evil for us to proudly declare ourselves to be the descendants of Yaakov. And I think some of the instinct to always brand Esav as evil emerges from the fact that Yaakov does some “sketchy” things: demanding his starving brother exchange his birthright for food, pretending he is Esav in front of his father to gain a blessing, among other things.

And the only response we offer is to reinterpret Esav as evil so as to legitimize everything that Yaakov does – but we don’t need to. Esav and Yaakov can be complicated. Indeed, I think there’s a lot we can learn from the fact that Yaakov is a fighter; he is someone who sometimes does things that are more gray than white.

And so, when you read Yaakov and Esav’s reunion this week, enjoy it. Read it as the beautiful story it is. We don’t need to decide in advance that Esav is evil and read every action he does as evil, too.

He can simply be a twin brother pained by the absence caused by a moment of anger and delighted to be reunited with Yaakov.

[1] There is a major debate over the correct way to refer to Lord Sacks. As it was once explained to me by someone I trust to know these things (I think it was you, Schwartz), technically speaking, the moment a person becomes a Lord, they lose all their other titles because all other titles are inferior to Lord. Similarly, they are no longer referred to by their first name. And so, “Rabbi Sir Jonathan Sacks” becomes “Lord Sacks.” But my understanding is that, because Lord Sacks’ legacy interacts so much with Jews outside the UK, the “brand equity” of his wider name is important. So he’s often called “Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks” despite the fact that that doesn’t make sense from the point of view of protocol.

[2] This may be a reference only I appreciate, because I enjoy watching people on YouTube make tier lists of “best Brandon Sanderson books” or “best starter Pokémon.” I am cool.