Moshe's Name Makes No Sense – Until We Realize It Isn't Jewish

On Egyptian royal naming conventions, folk etymologies, and the suspension of disbelief

I. Egyptian Names in the Torah

I’ve always been drawn to what I’d call “less traditional” arguments on the origins of some key Jewish names. It’s why, a few weeks ago in shul, I pointed out that the name Pharaoh gives Yosef, Tzaphnat Paneaḥ (Gen. 41:45), must be an Egyptian name (or, at least, a Hebraicized Egyptian name) – even though many Torah commentators offer interpretations based on Aramaic – because it doesn’t make that much sense to me for Pharaoh to be speaking any language other than Egyptian.

And it’s also why I mentioned that same Shabbat the fascinating argument of Rabbi Yaakov Kamenetsky that Yosef gives his son, Ephraim, an Egyptian name because, as R. Kamenetsky points out, it possesses the characteristic sound of other Egyptian names in the Torah, p/ph – such as Par‘oh/Phar‘oh, Potiphar, or Tzaphnat-Paneaḥ (Emet le-Ya‘akov, Gen, 48:5).

But my favorite example of this is also the most controversial – and it’s one we read about in Parashat Shemot: that Moshe’s own name is about as non-Jewish as could be.

II. The Torah’s Implausible Naming Story

I’ll start with the less-jarring version of the argument, made by the legendary 18th-century rosh yeshiva of Volozhin, Rabbi Naftali Tzvi Yehudah Berlin – better known by his acronym, the Netziv – in his Torah commentary Ha-Emek Davar (to Ex. 2:10).

The Netziv notes a glaring narrative issue with how the Torah describes Moshe’s naming:

וַיִּגְדַּ֣ל הַיֶּ֗לֶד וַתְּבִאֵ֙הוּ֙ לְבַת־פַּרְעֹ֔ה וַֽיְהִי־לָ֖הּ לְבֵ֑ן וַתִּקְרָ֤א שְׁמוֹ֙ מֹשֶׁ֔ה וַתֹּ֕אמֶר כִּ֥י מִן־הַמַּ֖יִם מְשִׁיתִֽהוּ׃

When the child grew up, she brought him to Pharaoh’s daughter, who made him her son. She named him Moses, explaining, “I drew him out of the water” (Ex. 2:10)

The entire premise of Moshe’s name, per the verse here, is that Pharaoh’s daughter named Moshe, “Moshe,” as a derivative of how she came to find him, ki min ha-mayim mishitihu, “I drew him out of the water.”

But Netziv’s problem here – and once you see it, you’ll never unsee it – is that the verse assumes that Pharaoh’s daughter, a princess of the greatest superpower and culture of its day, speaks Biblical Hebrew. And that makes no sense!

And Netziv is really bothered by this fact – and it’s something that, once you’ve realized it, becomes a really big problem. (Though I should note that many Torah commentators are bothered by it.) And while we might be tempted to try and answer by saying something to the effect of “while Pharaoh’s daughter didn’t speak Hebrew, she spoke a language similar enough to Hebrew that the derivation of the name ‘Moshe’ from the Egyptian version of ki min ha-mayim mishitihu still works,” it just can’t be true.

It would be true if it weren’t Pharaoh’s daughter but the daughter of a Canaanite king – as the Canaanite languages are all Semitic and all very similar to Hebrew. But, as Words of Myrrh’s resident expert on Biblical languages, Rabbi Dr. AJ Berkovitz reminded me, Egyptian isn’t a Semitic language. There’s no world in which Pharaoh’s daughter would have said anything in Egyptian even remotely similar to the phrase ki min ha-mayim mishitihu that would lead to a name sounding like Moshe when both were Hebraicized.

And there’s another issue, still – though Netziv himself doesn’t state it explicitly (even though it appears he’s circling the idea). I heard it from one of my Bible professors at YU, Dr. Aaron Koller, someone for whom Biblical Hebrew is very much his wheelhouse.1 And it’s a simple but profound point. Imagine Pharaoh’s daughter did speak Hebrew. Imagine she did say, ki min ha-mayim mishitihu and sought to derive the child’s name from it. That still would never get you the name “Moshe.” Even in this situation, it would only ever get you the name “Masui.”2

And, fascinatingly, Netziv refuses to accept a traditional solution here. Because the great 15th-century commentator Don Yitzḥak Abarbanel suggests that it was never Pharaoh’s daughter who named Moshe but Yokheved, Moshe’s mother – then serving as Moshe’s wetnurse. It was Yokheved who suggested that Pharaoh’s daughter use the name Moshe that Yokheved derived from ki min ha-mayim mishitihu.

And Abarbanel’s comment here has merit. It relies on some ambiguity in this verse, which simply states “she named him Moshe” – which could mean a different woman named him other than Pharaoh’s daughter – and it solves all the problems: because Yokheved would have spoken Biblical Hebrew (or, at the very least, a Semitic language of some sort).

Yet, Netziv rejects this because not only does it contradict Ḥazal in a midrash in which God explicitly tells Moshe that his name came from Pharaoh’s daughter (Vayikra Rabbah 1:3), but it also contradicts what Netziv refers to as derekh eretz – because the child is considered the child of Pharaoh’s daughter.

We thus confront the fact that, whatever the reason for Moshe’s name is, it’s not what the Torah itself says. Which leaves us with two key questions:

So, what is the origin of Moshe’s name?

Why would the Torah offer a counterfactual origin?

III. The True Origin of Moshe’s Name

Netziv’s own answer is to quote a Bohemian Rabbi Shmuel,3 who suggests that the name “Moshe” is an Egyptian one that means “child” or “boy.” This, Netziv explains, is because a son born into the Egyptian royal family was effectively the child of the entirety of Egypt – and thus “Moshe” is an Egyptian royal name (or, more accurately, the Hebraicized version of the Egyptian royal name).

This, as I said earlier, is the less-controversial explanation: Moshe’s name isn’t Jewish, it’s Egyptian – and he just has a generic Egyptian royal name befitting a grandson of Pharaoh.

But there’s a more controversial version of this that takes things a step further than Netziv. Because while it’s true that “Moshe” is an Egyptian royal name and that’s why Pharaoh’s daughter gave him a name befitting the grandchild of Pharaoh, it doesn’t mean “child” or “boy.” It doesn’t mean that the royal child is the child of Egypt.

Instead, the Egyptian word that gets Hebraicized into Moshe means “son of” – and this fits far better with Egyptian royal naming conventions. Because we can look at other examples of the names of Egyptian Pharaohs:

Ramses

Amenmose

Ahmose

Thutmose

And while these are just four examples, many different Pharaohs had these names, similar to the name “Henry” for the English monarchy.

And when we look at each of these names, we see that they can be broken down into two components. The second of which is key, some form of the name that in Hebrew is “Moshe” or in English is “Moses.” But it’s the first part of the name that’s striking:

Ra · MSES

Amen · MOSE

Ah · MOSE

Thut · MOSE

The first part of each name of Egyptian royalty is a member of the Egyptian pantheon – a god. Ra, the sun god. Amen (=Amun), the air god. Ah (=Iah), the moon god. Thut (=Thoth), also a moon god, though he seemed to have played other roles, too.

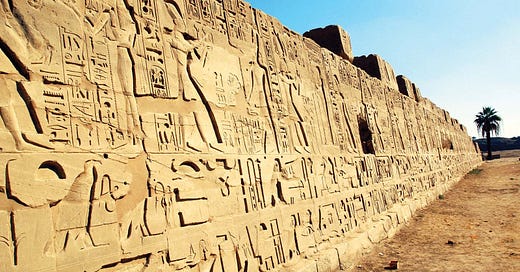

The name of each of these members of royalty illustrates a core aspect of Egyptian theology: that the Pharaohs are the sons of gods – and thus in some sense divine. Indeed, the hieroglyphical representation of the Pharaoh’s name – known as a cartouche – is an oval frame around a hieroglyph. In each of these royal names, the hieroglyph is the depiction of the Egyptian god.

All of which is to say that, when Pharaoh’s daughter gave the child she found a name, and the Torah preserves that as “Moshe,” it’s very likely that that is only half his name. What that other half was we could never know – but she named him in keeping with Egyptian convention, the son of an Egyptian deity.

And there’s a side point worth mentioning here, that the traditional name for Pharaoh’s daughter – though it’s never mentioned here in this story – is Batya or Bityah (cf. I Chron. 4:18, where we are explicitly told this is the name of [a different] Pharaoh’s daughter). Broken down, this name is “Bat” followed by one of God’s names. It could very well be that this is a Hebraicization of the Egyptian royal name, in which “Daughter of Egyptian deity” gets turned into “Daughter of the One God.” Indeed, Josephus calls Pharaoh’s daughter in our parashah Thermouthis, which means “daughter of” Ther (=Tharmuth), an Egyptian fertility deity.

IV. So, are you saying the Torah lied?!?!

If the realization of Moshe’s name being Egyptian wasn’t controversial enough, the corollary is that the Torah completely fabricates a rationale behind his name – leading to the awkward theological question of why it would do this.

And the Netziv addresses this issue in his comments both in our parashah and earlier, where the Torah explains why Adam and Ḥava called their son Shet – in English, Seth (Ha-Emek Davar, Gen. 4:25).

And the Netziv’s explanation is brief, but powerful. Translated from the Hebrew into the English, it might simply become “it’s a pun” – but there’s something far more profound here.

Because what Netziv recognizes is that, even when Biblical characters are ostensibly using Biblical Hebrew to derive the name of their child, the rationale the Torah offers to explain their name is often grammatically awkward, if not downright unsound. And though Netziv himself doesn’t use this term, he grasps that these are all “folk etymologies,” that the Torah’s goal is not to provide us with an accurate description of why the name was chosen but to teach a theological lesson. In our case, the Torah wants to draw attention to the miraculous nature of Moshe’s life – that he was saved by Pharaoh’s daughter – and so stresses that his name is linked to that.

(And additionally, when it comes to Moshe’s name, it’s not surprising that the Torah wouldn’t want its greatest prophet to bear the name of an Egyptian deity.)

V. Why this should be the opposite of controversial

There’s a point that I want to make that’s counterintuitive – especially if you’ve felt that all I’ve written has shaken your theological core – but it’s important.

Because, while we would never use this term when talking about the Torah, there’s often an element of our reading of it that requires us to “suspend our disbelief.” Definitionally, God performs miracles that are supernatural – and so, when we read of an entire river turning to blood, for example, we don’t really need to suspend our disbelief in the way that le-havdil elef havadalot, we need to when reading Brandon Sanderson’s Mistborn. But because miracles go against all our lived experiences, because they are so hard for us to imagine, the need to suspend our disbelief still lurks in the back of our mind.

And this means that when the Torah suggests something unrealistic – but, ironically, not because a miracle was performed but because something so mundane happened, like the naming of a child – that completely conflicts with what we know, it becomes a greater challenge to suspend our disbelief. Pharaoh’s daughter could not have spoken Hebrew, and to insist we believe that is to demand a tremendous suspension of our disbelief.

Realizing Moshe had an Egyptian name, then, actually anchors the plausibility of the story more. Because, of course he would have an Egyptian name! Rather than seeing the Egyptian origin of Moshe’s name as a problem, it’s actually a solution.

Sometimes, it’s precisely the “controversial” stuff that offers better answers to the questions we have.

His PhD dissertation sounds like the most boring subject ever studied – though one that illustrates just how much expertise he has on Biblical Hebrew, The ancient Hebrew semantic field of cutting tools: A philological, archaeological, and semantic study.

Dr. Koller’s point was obviously confirmed by Words of Myrrh’s resident expert on Biblical languages, Rabbi Dr. AJ Berkovitz.

Netziv refers to him as coming from בעהיים, and all Googling that gets you is lots of people quoting the Netziv – but I think it transliterates to “Bohime,” i.e., Bohemia, but I could be wrong.