Welcome to the alliteratively and delightfully entitled Qontroversial Questions on the Parashah (it’s still pronounced “Controversial” – I just think I’m being qlever!) Subscribe to continue to receive these and please share with those you think would be interested.

I. The Awkward Placement of Vayikra

There is something very strange about Sefer Vayikra – though it’s only noticed by ignoring it.

Because Sefer Shemot ends by telling us how the Jewish people’s movements were dictated by the cloud or fire that hovered over the Mishkan (Ex. 40:36–38), which the Torah then repeats a chunk of chapters into Sefer Bamidbar (Num. 9:15–17). And only a few verses after this, the Jewish people embark on their first journey (Num. 10:33).

And this means that if you omitted Sefer Vayikra (and the beginning of Sefer Bamidbar), you could seamlessly flow from the end of Sefer Shemot into Sefer Bamidbar without ever needing Sefer Vayikra. Now, I’m not saying that Sefer Vayikra shouldn’t be in the Torah – but I am saying that there isn’t any narrative need for Sefer Vayikra to be here.

Indeed, other than telling us about the inauguration of the Mishkan and the curious narrative about the blasphemer – about which I had an article published on The Lehrhaus last year – there aren’t any narratives at all in Sefer Vayikra. It wouldn’t be too shocking, then, for there to be an alternative universe in which the inauguration of the Mishkan was the concluding narrative of Sefer Shemot and Sefer Vayikra was located somewhere else.

In other words, while the flow from Sefer Bereishit to Sefer Shemot is a given – and it’s obvious why Sefer Devarim follows from Sefer Bamidbar – Sefer Vayikra looks awkwardly crowbarred into the Torah at this point.

And, perhaps, that’s actually the whole point.

II. The Different Perspectives of the Torah

Something we rarely consider is the “voice” in which a given section of the Torah is written in. But when it comes to four of the five Sefarim of the Torah, it’s not too hard to figure out.

The perspective of Sefer Devarim is obvious. It begins, “these are the words that Moshe addressed to all of Israel” (Deut. 1:1) – Sefer Devarim is written from Moshe’s perspective in Moshe’s voice.

Bereishit, Shemot, and Bamidbar are a little trickier – but only because we don’t typically think about the Torah having a narrator. But if you take a moment, it’s clear that these books are all written from the distant perspective of a third-person narrator. God is treated, le-havdil, like all the other “characters” in the story.

But it’s much harder to pin down the voice or perspective of Sefer Vayikra. And the challenge begins with its opening verse, which frames things in a jarring way.

Usually, when the narrator of the other books in the Torah wants to tell us that God spoke to Moshe, it uses the classic phrase (used around eighty times in the Torah), “God spoke to Moshe, saying” which presents the conversation between God and Moshe as a seamless, single moment: God just spoke to Moshe.

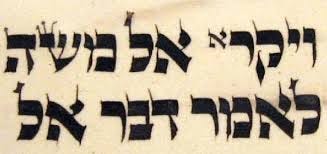

But that’s not how Vayikra opens. Instead, it gives us two different stages in the conversation between God and Moshe. First, it tells us that “God called to Moshe,” after which it tells us, “and spoke to him from the Tent of Meeting, saying” (Lev. 1:1). That the cantillation places an etnaḥta – the strongest possible type of pause – on the first clause here only heightens the sense that there are two different things happening in the verse: first there is a summons to Moshe, only after which Moshe arrives and the conversation begins.

And even what I just wrote assumes a crucial detail not explicitly stated by the Torah. Because the first part of the verse doesn’t actually say anything about God. It’s simply vayikra el-Moshe, “and he called to Moshe” – it’s only the second half, vaydabber Hashem ēlav, “and God spoke to him,” that makes it clear that vayikra el-Moshe is not “and he called to Moshe” but “and He called to Moshe.”

And further issues with Sefer Vayikra abound – ones that are particularly heightened by the current time in the Jewish year we find ourselves. Because not only did we just finish Sefer Shemot – which, after painstakingly relating every aspect of God’s command to build the Mishkan, then painstakingly relates every aspect of Moshe and the people fulfilling that command – but we’re also in the run-up to Pesaḥ.

And the laws of Pesaḥ described in Parashat Bo are fascinating because they are examples of, not only God commanding something that is then put into practice by the Jewish people, but also of Moshe conveying and reframing God’s commandments to the people.1

All of which is to say that the typical flow in the Torah we’ve seen in Sefer Shemot is for God to state His commandments to Moshe, who then relates it to the people, who then go ahead and do it – all of which is reported by the Torah.

But Sefer Vayikra is different. Look at these examples:

This shall be to you a law for all time: to make atonement for the Israelites for all their sins once a year. And Moses did as the LORD commanded him. (Lev. 16:34)

Thus Moses spoke to Aaron and his sons and to all the Israelites. (Lev. 21:24)

So Moses declared to the Israelites the set times of the LORD. (Lev. 23:44)

All of these verses occur at the end of a section – and offer a completely contrasting portrayal than what we are used to in Sefer Shemot. Rather than what I wrote above, all Sefer Vayikra reports is what God told Moshe, followed by a quick note that effectively states “and Moshe did it.” There is narry a mention of what Moshe said himself nor of the people following the laws.

III. The Unique Perspective of Sefer Vayikra

Many years ago, I came across a fascinating answer to these questions by Rabbi Shimon Klein, a prominent Tanakh teacher in Israel – though I’m going in a slightly different direction than he does.

He argues that Sefer Vayikra is the one book in the Torah written from God’s own perspective (as it were). To be more precise, it’s still written by a narrator – as God is still a “character” – but it’s a different narrator, one whose focus is on God rather than Moshe and humans.

And that’s why Sefer Vayikra opens by relating God and Moshe’s interaction so differently.

Because if you think about the 80-ish instances of “God spoke to Moshe, saying,” it is very loose with the details. All the narrator wants to do is provide us with one necessary narrative point so that everything else makes sense. We need to know that God spoke to Moshe, but the mechanics of how that happened aren’t important. Because the narrator is interested in the actions of human beings – and all that matters is simply that Moshe was told things by God.

But Sefer Vayikra gives us a window into how “God spoke to Moshe, saying” worked from God’s end. That it begins by assuming we know the perspective, “and He called to Moshe” underscores this: we don’t need to know who is doing the calling because it’s God’s perspective. And so, it lets us know that when God wanted to speak to Moshe, He first summoned him to the Tent of Meeting before giving him instructions.

And this also explains why Vayikra has very few narratives.2 Because the narratives are all about how humans followed God’s command – but that’s not the perspective of Sefer Vayikra. Indeed, this is why we just get the simple summaries of Moshe following through. Because, from God’s perspective, what matters is that Moshe did as He commanded. That’s all that needs to be noted.

And the strongest indication of all of this is how many of the mitzvot in Sefer Vayikra are framed from God’s perspective:

Speak to the Israelite people and say to them: I, the LORD, am your God. (Lev. 18:2)

You shall keep My charge not to engage in any of the abhorrent practices that were carried on before you, and you shall not defile yourselves through them: I, the LORD, am your God. (Lev. 18:30)

Speak to the whole Israelite community and say to them: You shall be holy, for I, the LORD your God, am holy. (Lev. 19:2)3

When you reap the harvest of your land, you shall not reap all the way to the edges of your field, or gather the gleanings of your harvest. You shall not pick your vineyard bare, or gather the fallen fruit of your vineyard; you shall leave them for the poor and the stranger: I, the LORD, am your God. (Lev. 19:9–10)

You shall not falsify measures of length, weight, or capacity. You shall have an honest balance, honest weights, an honest ephah, and an honest hin. I, the LORD, am your God who freed you from the land of Egypt. (Lev. 19:35–36)

But the land must not be sold beyond reclaim, for the land is Mine; you are but strangers resident with Me. (Lev. 25:23)

Fascinatingly, a lot of these mitzvot have parallels in Sefer Devarim – and comparing them really sharpens the difference in perspective. To use just one example, compare Lev. 19:9–10 above with the version Moshe states in Sefer Devarim:

When you reap the harvest in your field and overlook a sheaf in the field, do not turn back to get it; it shall go to the stranger, the fatherless, and the widow – in order that the LORD your God may bless you in all your undertakings. When you beat down the fruit of your olive trees, do not go over them again; that shall go to the stranger, the fatherless, and the widow. When you gather the grapes of your vineyard, do not pick it over again; that shall go to the stranger, the fatherless, and the widow. Always remember that you were a slave in the land of Egypt; therefore do I enjoin you to observe this commandment. (Deut. 19–22).

While the entire justification for mitzvot in Sefer Vayikra is “do it because I, God, said so,” the framing in Sefer Devarim adds two crucial pieces. The first is the promise of blessing, “I’ll reward you if you do it” – something that humans need for motivation but God doesn’t need to demand the law. The second is the appeal to human sentiments: “Do this because you were once mistreated and know what that is like.”

To use the classic parent-child analogy here, when I yell at tell my kids to tidy their room, from my perspective there is no need for anything more than my instruction. I don’t like it to be messy, I know that it’s bad to have a messy room – but that’s not convincing for them.

But to convey it to them I must offer threats and punishments prizes and rewards. And I must appeal to their better natures, “if you don’t do it, Imma or I will have to do it and we’ll throw everything in the garbage.”

And this perspective also solves a thorny challenge in Sefer Vayikra: the deaths of Nadav and Avihu. While there’s much to say here, the problem is raised by the Torah’s lack of information regarding their death:

“They offered before the LORD an alien fire that they had not been commanded. And a fire came forth from the LORD and consumed them, thus they died at the instance of the LORD” (Lev. 10:1–2)

But if we see Vayikra as coming from God’s perspective, well, it’s humans that need things explaining and that’s not the perspective here. From God’s perspective, it is obvious why they must die and so the Torah just reports it happening.

IV. But Why Here?

None of what I’ve wrote actually solves the question that I opened with: why is Sefer Vayikra crowbarred into this part of the Torah?

But I think that understanding that it’s written from God’s perspective (as it were) illuminates exactly why it is crowbarred into the Torah here.

Because the Mishkan was built to be a house for God – it represents a shift in the relationship between the Jewish people and God. He is no longer just their Redeemer, the Being who brought them out of captivity, but He is now their God to worship.

And so, the Torah gives us a window into God’s personality, as it were. In order for the Jewish people to forge a relationship with Him, they need to establish two things. The first is that they can achieve a glimmer of understanding – so many verses relate things from God’s perspective. But even more significantly, there needs to be a realization that God can never be truly understood by humans.

Sefer Vayikra thus provides us with an understanding of God, while at the same time forces us to realize how little we can understand.

The subject of my Shabbat Ha-Gadol Derasha this year. 4:30 PM, followed by Minḥa – babysitting provided.

Indeed, those narratives and some other parts have a different narrator (or have the regular narrator of Vayikra along with another).

The first verse actually states “God spoke to Moshe, saying” which doesn’t defeat the entire point here – it just reinforces what I wrote in the previous footnote.