Along side Qontroversial Questions on the Parashah I’m also going to be sending out eight Haggadah ideas in the run up to Pesaḥ – This is the first!

(there’s a chance I forget to delete “This is the first!” for the next few)

In his Haggadah, Rabbi Yeḥiel Mikhel Epstein – the great 19th-century Russian rabbi best known for his Arukh ha-Shulḥan – makes a simple observation that had never crossed my mind before yet really got me thinking.

Because while we’re all familiar with the iconic capstone to the Seder – the declaration le-shana ha-ba’ah biyrushalayim, “next year in Jerusalem” – I’d never noticed before that we also begin the Seder proper with effectively the same statement.

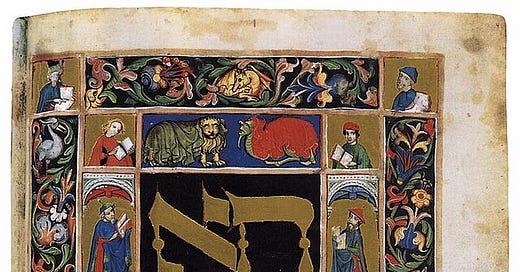

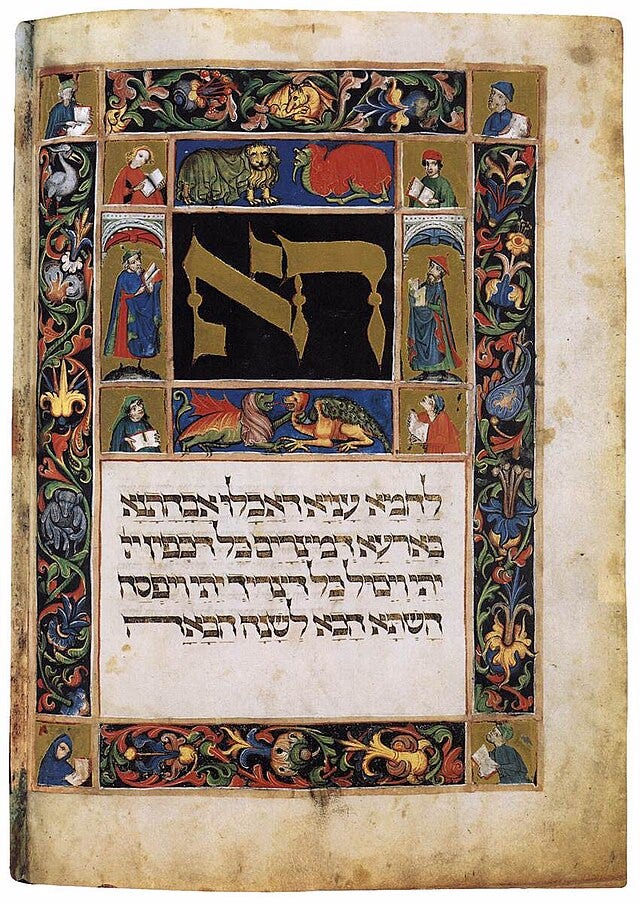

As we begin Maggid and recite the passage of Ha Laḥma Anya, we say that hashata hakha, “now we are here;” le-shana ha-ba’ah be-ar‘a de-yisrael, “next year in the Land of Israel.”

And what this means is that the bulk of the Seder is bookended by similar declarations hoping to celebrate Pesaḥ in Israel the following year at a rebuilt Beit ha-Mikdash. And R. Epstein has a fascinating explanation (though I do think it’s a bit jarring and I did wrestle with whether to share it because it also quite an awkward understanding).

It all starts by recognizing that, as hard as preparing for Pesaḥ is on everyone, Pesaḥ is a festival that’s particularly hard on a specific group of Jews – the very Jews who are the subject of Ha Laḥma Anya:

כָּל דִכְפִין יֵיתֵי וְיֵיכֹל, כָּל דִצְרִיךְ יֵיתֵי וְיִפְסַח.

Let all who are hungry come and eat; let all who are needy come and join us for the korban pesaḥ.

After all, so many halakhot that govern our Pesaḥ preparation are designed to help those in need: there is the obligation of ma‘ot ḥiṭṭim, literally “money for wheat” – a special mandate to give tzedakah to those who will need help affording Pesaḥ (Rama, O.Ḥ. 429:1). Similarly, the Mishnah demands that special charitable considerations be given to the poor to ensure they can drink all four cups of wine (mPes. 10:1).

But the Arukh ha-Shulḥan recognizes that while for many, the moment Pesaḥ begins, some calm is finally restored – for those in need, the subjects of Ha Laḥma Anya, the potential for pain is not yet over.

Because what happens is that the needy are invited to other people’s Sedarim. And while that’s a good thing – not for one moment does R. Epstein think this is a problem – it presents a potential psychological challenge.

Sitting around the table, it can become all too clear who has been invited for ḥesed and who has not – and there is no point at the Seder at which this is more acute than the declaration about those in need, Ha Laḥma Anya.1

And for that reason, he suggests, Ha Laḥma Anya included a line specifically for those in need at the table: “next year in the Land of Israel.” It exists, he thinks, to serve as a pseudo-prayer and a source of inspiration. Lest someone in need at another’s Seder feel despondent – it can be hard for people to shake the sense that they are being given ḥesed – they have an opportunity to ask God for redemption from their situation, specifically by referencing our Exodus from Egypt, the ultimate example of redemption.

I think that this is a powerful message for us all to reckon with at the Seder this year – for two reasons.

The first is that, as much as we celebrate ḥesed in our communities – and we must continue to do so – we risk seeing those we help as nothing more than the cogs we must crank so that we can have performed ḥesed.

A true sensitivity to those in need, however, begins by trying as hard as possible to not making them feel in need. Ruthy is, admittedly, much better at this than I am, but it’s about making sure that there’s no way to divide the Seder into “family” and “guests” – it must be nothing other than “all of us” together.

But there’s another dimension to all of this highlighted by R. Epstein’s comments. Because if the first declaration of “next year in the Land of Israel” is for those who don’t enjoy the Seder, I think the second declaration at the end is for those who do.

For people for whom the Seder is a beautiful family time – is one of the most cherished Jewish experiences of the year – they still need to reckon with the definitional imperfection of a Seder without a Beit ha-Mikdash. Thus, everyone recites at the end, “next year in Jerusalem.”

Because no matter how wonderful the Seder was, if it’s not in Yerushalayim as part of the service of the Beit ha-Mikdash it can never be a truly enjoyable Pesaḥ.

I like to think that the Arukh ha-Shulḥan was once at a Seder where someone else nodded at a person in need during Ha Laḥma Anya and that scarred R. Epstein.