The Most Important Day of the Year That You’ve Never Heard Of

And the strangest quirk of the Jewish calendar

Welcome to the alliteratively and delightfully entitled Qontroversial Questions on the Parashah Week Before Shavuot (it’s still pronounced “Controversial” – I just think I’m being qlever). Subscribe to continue to receive these and please share with those you think would be interested.

I just had an article published on The Lehrhaus! It’s about the prohibition of counting Jews and the mathematics behind it – if you’ve wondered what QQotP would look like if it were rigorously edited, this is a good example.

I. Any Excuse to Not Say Tahanun is a Valid Excuse

Last year, a member of my shul discovered a website that told you whether or not you needed to say taḥanun on that day. But herein lay his problem: he discovered the website on the 2nd of Sivan. And while the website confidently told him that no taḥanun was said that day, the reason confused him and made him suspicious about the whole thing. Because it claimed that the 2nd of Sivan was a special day – though one he’d never heard of: “Yom ha-Meyuḥas.”

And my response to his request for clarity didn’t exactly help assuage his fears that the website was making things up. Because while I told him that it’s true that we don’t say taḥanun on the 2nd of Sivan and that yes, it is Yom ha-Meyuḥas, I could only provide him with an unhelpful explanation: “it’s a thing but not really a thing.”

Because what makes Yom ha-Meyuḥas – which, if you’re reading this on the Wednesday it comes out, is tomorrow – so fascinating is that it really doesn’t have much of an explanation. It’s a day on the Jewish calendar that just is. Indeed, the Ezras Torah Luach I checked this morning simply stated that there was no taḥanun on the 2nd of Sivan because it’s Yom ha-Meyuḥas – and that was it.

And while few of us feel a need to be confident in why we’re not saying taḥanun – we’ll take any possible justification – the existence of Yom ha-Meyuḥas raises a profound question about the Jewish calendar.

Just what on earth is this day?

II. A Guide to Sivan for Those Who Hate Tahanun

For most people who don’t enjoy saying taḥanun, the month of Sivan provides a welcome reprieve – as many communities refrain from saying taḥanun for the first twelve days.

But there are very specific reasons why we don’t say taḥanun on these twelve days – and understanding them is crucial for appreciating Yom ha-Meyuḥas.

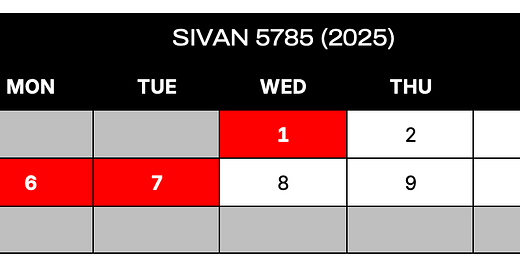

Let’s start with the obvious days we skip taḥanun, highlighted in red:

We skip taḥanun on the 1st of Sivan because it’s Rosh Ḥodesh and on the 6th and 7th because it’s Shavuot. Now, these aren’t Sivan-specific reasons per se, they’re just the Sivan-specific application of general rules: We skip taḥanun on Rosh Ḥodesh and festivals.

So far, so easy.

Now let’s focus on the next simplest to explain, the 8th.

This, again, is similar to the above. It doesn’t have anything to do with Sivan itself, just the fact that a festival occurred in Sivan. Because the day after every Yom Tov – known as Issru Ḥag (cf. Ps. 118:27) – is a day to which Ḥazal ascribed significance (Sukkah 45b), encouraging one to treat Issru Ḥag as a joyous day. In other words, it’s another day on which to avoid taḥanun.

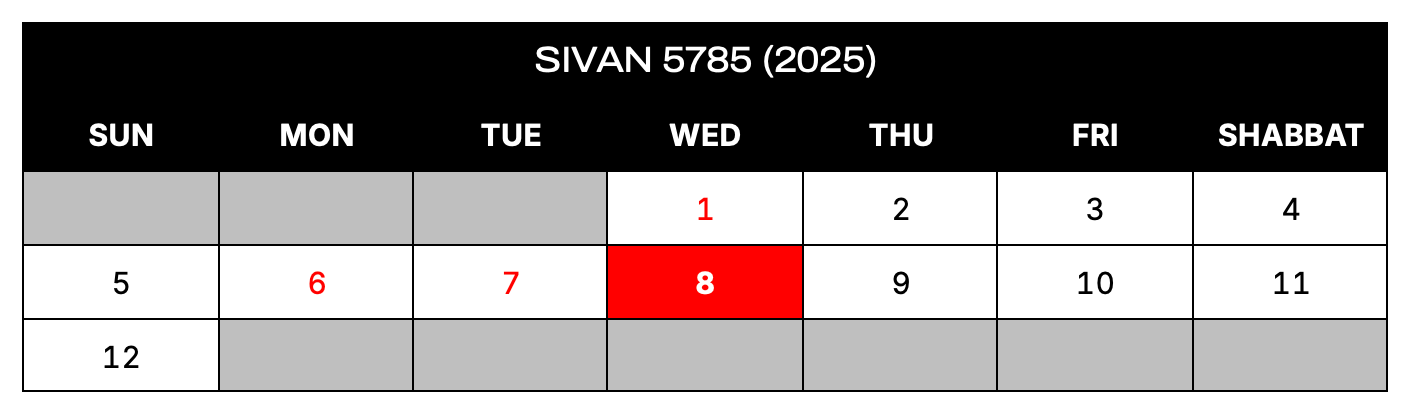

And while some communities resume taḥanun on the 9th of Sivan1 – thus requiring specific explanations for why we don’t say it on the 6th–8th – many refrain from taḥanun for the entire seven days spanning the 6th–12th of Sivan:

Yet this is for a more Sivan-specific – or more accurately, Shavuot-specific reason – rooted in the halakhic principle known as tashlumin.

As the Mishnah explains and the gemara elaborates, though a person had an entire week to make a pilgrimage and offer sacrifices on the other two pilgrimage festivals, Sukkot and Pesaḥ, a person only had the one day of Shavuot itself. Because this increased the likelihood that a person would miss the opportunity to appear in the Beit ha-Mikdash on Shavuot, the same week-long period was applied to Shavuot to allow a person more time (mḤag. 1:6; Ḥag. 17a).

We thus treat this entire seven-day period of tashlumin, from the 6th–12th of Sivan, as a joyous time on which no taḥanun is said.

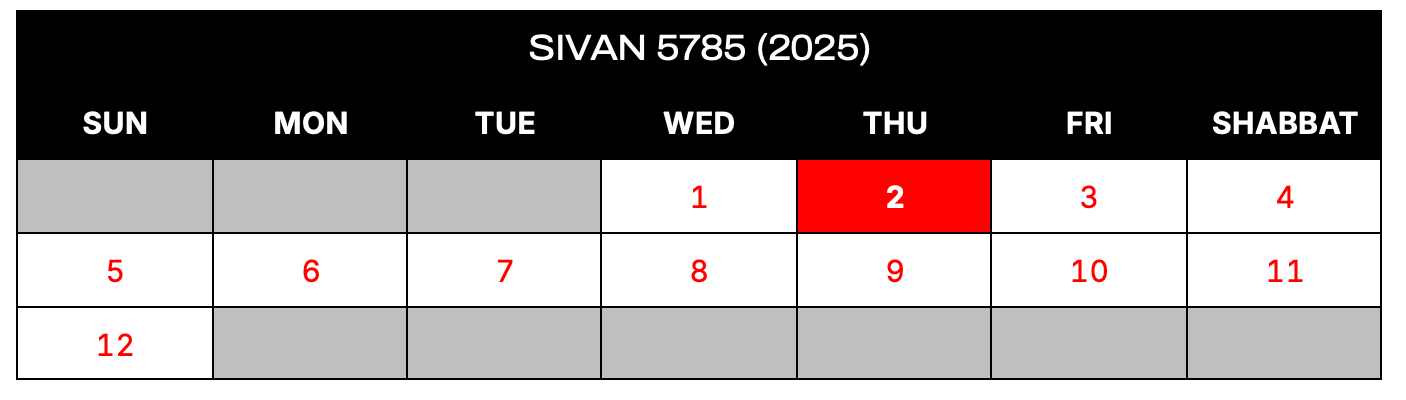

But this still leaves us needing to account for four no taḥanun days: the 2nd, 3rd, 4th, and 5th of Sivan – and for three of these it’s really easy (and, again, Sivan/Shavuot-specific) reason:

It stems from our celebrating Shavuot as the anniversary of the giving of the Torah. Because we extend that joy to the three days before Shavuot, too, because they are the anniversary of the sheloshet yemei hagbala, the three days of preparation Moshe demanded of the people before receiving the Torah (Ex. 19:15). And thus no ṭahanun is said on these days, too.

And all of this leaves us with just one day in Sivan for which there is no obvious explanation as to why no taḥanun is said: the 2nd of Sivan.

Yet here there is actually a really simple and clear reason why we don’t say taḥanun that’s printed in every luaḥ: because it’s Yom ha-Meyuḥas!

In other words, the ease with which we can explain why we don’t say taḥanun for eleven of the first twelve days of Sivan only amplifies the confusion regarding why we don’t say it on the 2nd!

And here, there isn’t really much of an explanation.

III. Yom ha-Meyuhas

At this point, you may be wondering what the term Yom ha-Meyuḥas means – maybe I’ve been intentionally refusing to translate it because then it will all make sense.

So feel free to stop reading at this point if knowing that the translation of Yom ha-Meyuḥas helps explain it all.

It means “Privileged Day.”

…

Yep. It really doesn’t help.

All that we know about the day on which we don’t say taḥanun for no clear reason is that it was named “the privileged day.” It’s as though the Jewish calendar is simply saying, “Of course you shouldn’t say taḥanun on a privileged day – that’s obvious!”

And, in truth, there is a part of the story that ends here. Because you could offer a very unkind understanding of Yom ha-Meyuḥas: that it exists simply to excuse us from saying taḥanun for the full 12 days. Otherwise, we’d stop on Rosh Ḥodesh, say it for one day, and then just not say it again. So, rather than do that, we invented a day, Yom ha-Meyuḥas, to justify no taḥanun.

But there are some fascinating suggestions as to what makes Yom ha-Meyuḥas special. And I must give full credit to QQotP reader Chaim G. for telling me about Yom ha-Meyuḥas – and sharing with me an article his father wrote about it – many years ago.

The first explanation for Yom ha-Meyuḥas emerges from a principle explained by Ḥazal: “Any day positioned between two holidays is treated as a holiday in its own right” (Taʿanit 18a). It should be stressed that Ḥazal are not discussing Yom ha-Meyuḥas – otherwise accounting for it would be easy – but the idea seems to apply here. Because the 2nd of Sivan is sandwiched between two days considered joyous enough to not say taḥanun, Rosh Ḥodesh and the 3rd of Sivan, it inherits their non-ṭahanun saying property.

This rationale works with some of the explanations above: There’s nothing specific to the 2nd of Sivan itself; it just happens to be a day sandwiched between two other days.

But a different suggestion is to ascribe Shavuot-specific significance to the 2nd of Sivan, one that relates to the reason we don’t say taḥanun for the three days before Shavuot. Because, just as these days are the anniversary of a key period before the giving of the Torah, the 2nd of Sivan is, too.

Per Ḥazal, God commanded the people to become a “kingdom of Priests and a holy nation” on the 2nd of Sivan (Ex. 19:16; Shabb. 86b). Due to the Shavuot-specific significance of this mandate-defining command, we don’t say taḥanun.

But there is a third, deeply curious suggestion explaining the significance of Yom ha-Meyuḥas that comes from the great 19th-century Russian Rabbi Yeḥiel Mikhel Epstein in his Arukh ha-Shulḥan. After suggesting the gemara in Taʿanit mentioned above as a source, he then writes that Yom ha-Meyuḥas is special: “because Yom Kippur falls on this day” (O.Ḥ. 494:7).

At first, this seems a cryptic line – because Yom Kippur is definitely not tomorrow. I double-checked.

But it turns out that this statement relates to one of the most interesting calendrical quirks of the Jewish calendar – and one that redefines the meaning of Yom ha-Meyuḥas.

IV. Calendar 101

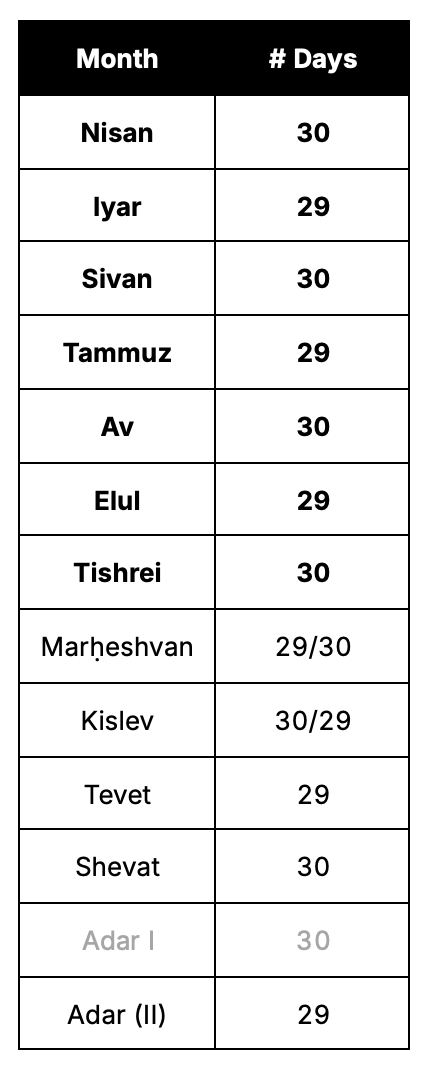

The Jewish calendar is fascinating, as, unlike the secular calendar, it has a surprising amount of variability in the number of days a year can contain. In a non-leap year, you can have between 353–355 days in the year, while a leap year can have between 383–385.

But, as much variance as this is, it’s not haphazard. Because a normal year has a relatively predictable pattern. If we consider the Jewish year to begin in Nisan, then the number of days in a month always oscillates from Nisan–Tishrei. Nisan always has 30 days, Iyyar always has 29 days, etc.

After Tishrei, however, things change. The months of Marḥeshvan and Kislev can have a different combination of days – either both 29, both 30, or oscillating like all the other months. I don’t want to get into the reasons why, but it’s done to rig the calendar to ensure that something like Yom Kippur doesn’t fall on a Friday or Sunday.

And then, obviously, we have what happens in a leap year: An entire additional 30-day month is added to the calendar.

But there’s a surprisingly obvious yet fascinating observation here. While there is some fluctuation in the Jewish calendar, the months of Nisan–Tishrei are pristine: they are predictable and will never change.

And it just so happens – though of course this is intentional – that all the Biblically-mandated festivals fall during this period. From the beginning of Pesaḥ to the end of Simḥat Torah there will always be the exact same number of days, no matter what else is happening in the calendar:

And the most obvious example of this is when Shavuot itself falls: always the day after the first day of Pesaḥ, seven weeks later.

But this also means that Shavuot will always be the same day of the week as the second day of Pesaḥ was. The second day of Pesaḥ was a Sunday night/Monday this year – and thus Shavuot is, too.

But you can do more than this. It turns out that, because Pesaḥ is over a week long, there are always the same number of days from Pesaḥ to anything else between Pesaḥ and Tishrei.

And this means that you can take any date in the Jewish calendar, and find a stretch of days between it and one of the days of Pesaḥ that divides by seven.

Let’s take Yom Kippur as an example.

The 10th of Tishrei is the following number of days from each of the days of Pesaḥ:

As you’ll see, only one of these is perfectly divisible by seven: 168. Which means that Yom Kippur will always fall exactly twenty-four weeks after the 5th day of Pesaḥ.

In fact, each of the other Biblical holidays (plus Tisha be-Av and Yom Haatzmaut) corresponds to a specific day of Pesaḥ:

But here’s the thing. Because if the second day of Pesaḥ corresponds to Shavuot, it means we can superimpose Sivan on top of Pesaḥ – though with a few tweaks.

First, we’ll make Pesaḥ II correspond to the 6th of Sivan, Shavuot.

Next, let’s note that, as I mentioned before, Pesaḥ V corresponds to Yom Kippur.

But if you look at the calendar, something becomes very obvious: Not only does Yom Kippur always fall on the same day as Pesaḥ V, but Yom Kippur, Pesaḥ V, and the 2nd of Sivan will always fall on the same day of the week:

And that’s what the Arukh ha-Shulḥan meant! Yom ha-Meyuḥas is the same day of the week that Yom Kippur will fall!

V. Yom ha-Meyuhas Kippur

Now, as strange as it is to connect Shavuot and Yom Kippur, there’s what to say. Because while we celebrate the giving of the Torah on Shavuot, that was only the first set of luḥot – the ones Moshe broke upon witnessing the Sin of the Golden Calf.

The second set were given on – according to Ḥazal in many places quoted by Rashi (Ex. 33:11) – you guessed it, Yom Kippur.

But here’s the kicker. In the repetition of the Mussaf Amidah on Yom Kippur, we refer to Yom Kippur as:

יוֹם מִיָּמִים הוּחָס. יוֹם כִּפּוּר הַמְּיֻחָס.

The most privileged day of all days. Yom Kippur that is privileged.

Yom Kippur is the Yom ha-Meyuḥas. That we refer to the 2nd of Sivan the same way only reinforces the connection.

And it’s this that led R. Yosef Ḥayyim Zonnenfeld to have the practice of treating the 2nd of Sivan as the beginning of the High Holiday period (Sefer Torat Ḥayyim, Hilkhot Sefirat ha-Omer ve-Ḥag Shavuot §7 [p. 93]).

All of which is to say that tomorrow we won’t say taḥanun for a seemingly made-up reason – where the calendar fabricated a day. But, by doing so, it kicks off the holiest time of the year.

For reasons, I can only assume have something to do with a general resistance towards all forms of joy.