Along side Qontroversial Questions on the Parashah I’m also going to be sending out eight Haggadah ideas in the run up to Pesaḥ

Long before I started Qontroversial Questions on the Parashah and tens of people – tens! – began subscribing to read my random musings and surprisingly-strongly-held-opinions on the minutiae of the parashah, I started this Substack to share brief ideas on the Haggadah (that eventually got longer and longer, which at this point is my M.O.) with my shul in the run up to Pesaḥ.

I came up with the name Words of Myrrh as I felt it was a perfectly optimized name for people to memorize and thus share with others, who could then confidently and effortlessly type it into Google to find the Substack. To be honest, the fact that I was even able to register a brand with the word “myrrh” in it was a surprise – I just couldn’t believe that no one else had thought to capitalize on the word “myrrh!”1

But long before I started the Substack, I would record my ideas and send them to a WhatsApp group (where I also sent pre-Seliḥot ideas for a couple of years).

And I mention all of this brief history because, while Words of Myrrh has only become a thing most of you have been following for at best the past six months, my mental history of the project is much longer. And so, I often find myself routing around the Words of Myrrh Archives (which is a very dramatic way to frame the files scattered around my Mac and Google Drive) to figure out if I’m repeating myself.

And that’s what happened a couple of weeks ago when writing Qontroversial Questions on the Parashah. I was certain that I must have shared something that I believe to be one of the most powerful ideas I’ve ever read on the Haggadah – but I couldn’t find it anywhere on Words of Myrrh, save a reference to it in my Haggadah recommendations from a couple of years ago, which you can read here:2

It turns out that I had shared it four years ago as one of the audio Haggadah ideas on WhatsApp. And, reading the transcript, I don’t think I did it justice (which is also very frustrating for me because I can’t just copy-and-paste the transcript and effortlessly send out another Haggadah idea). So here is a much better rendition of the idea in writing.

The Mishnah (mPes. 10:4) insists that the focus of Maggid must be an exposition on the passage, Arami Oved Avi, taken from Parashat Ki Tavo – which details the declaration a person must make when bringing their first fruits to the Beit ha-Mikdash (Deut. 26:5–9).3 And that’s why a large part of the Haggadah is devoted to a verse-by-verse exposition of the declaration.

We thus read the verse:

וַיָּרֵ֧עוּ אֹתָ֛נוּ הַמִּצְרִ֖ים וַיְעַנּ֑וּנוּ וַיִּתְּנ֥וּ עָלֵ֖ינוּ עֲבֹדָ֥ה קָשָֽׁה׃

The Egyptians dealt harshly with us and oppressed us; they imposed heavy labor upon us. (Deut. 26:6)

And on this final clause, that the Egyptians “imposed heavy labor upon us,” the Haggadah elaborates by referencing a verse from Parashat Shemot:

וַיַּעֲבִ֧דוּ מִצְרַ֛יִם אֶת־בְּנֵ֥י יִשְׂרָאֵ֖ל בְּפָֽרֶךְ׃

The Egyptians put the Israelites to work at crushing labor. (Ex. 1:13)

And here, in his Haggadah entitled Go Forth and Learn, Rabbi David Silber devotes two pages (in which the font is printed at a really tiny size) to exploring what this means.

And, for me, it’s one of the most incredible and impactful ideas I’ve ever read.

It starts by recognizing the meaning of the word the Torah uses to describe the work that the Jewish people were subjected to in Egypt, parekh. As R. Silber notes, Biblical scholars connect this to the concept in the Ancient Near East known as pirkhu: forcing free people to perform slave work.

This, he stresses, aligns with Ḥazal’s interpretation, that the Egyptians didn’t just enslave the Jewish people but intentionally selected the wrong slaves for the task (Soṭah 11b). A Jew who was clearly weak and feeble, for example, would be forced to carry heavy loads.

In other words, Pharaoh’s goal for his slave workforce was never productivity – contrary to popular belief, the goal was never to really build things of note, and definitely not the pyramids – but was to simply inflict the maximal possible pain.

And this understanding is reinforced by Pharaoh’s willingness to make it harder for the Jewish people to work by removing their building materials as punishment (Ex. 5:6–19). Had Pharaoh’s ultimate goal been the completion of projects by his Jewish slave force, he would never have intentionally done something to limit their ability to build.

All of which is to say that the parekh, the slave work of the Jewish people, was never about achieving anything and only ever about causing as much pain as possible – both physical and psychological.

And this is where R. Silber makes an astounding observation.

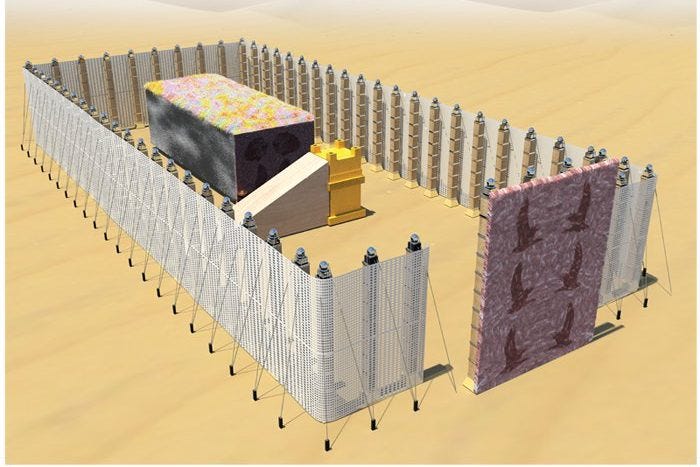

Because, after 210 years of brutal slavery – being made to suffer for the sake of suffering – the Jewish people are freed, and God commands them to build the Mishkan, a project that was the complete opposite experience of their slavery in Egypt.

First, it had, not just any purpose, but the most rewarding purpose: to build a home for God on earth, “And let them make Me a sanctuary that I may dwell among them” (Ex. 25:8). Unlike their slavery which was intentionally unproductive, the building of the Mishkan could not have had a more productive purpose.

Second, unlike the forced labor of slavery, the Mishkan’s construction was voluntary: in His opening command regarding its construction, God explicitly requests that only people asher yidvennu libbo, “whose heart is so moved,” participate (Ex. 25:2). Indeed, words emerging from the root n-d-v for voluntary acts recur throughout the Torah’s description of how God commanded the people to build the Mishkan.

Third, in addition to the reference to parekh, the Torah constantly uses the word ‘avodah to describe the Jewish people’s work as slaves. But, in contrast, it describes their work building the Mishkan as melakhah. Now, on the surface, both of these mean “work” – but there is a key difference.

Because not only is melakhah also used by the Torah to describe God’s creation of the world (Gen. 2:2–3), but Ḥazal added a modifier in the context of the Mishkan. Noting the juxtaposition of the command of Shabbat and the construction of the Mishkan, Ḥazal famously derived that the prohibited acts on Shabbat – the 39 melakhot – are so prohibited because they were the activities used in constructing the Mishkan. And here, Ḥazal specifically characterize them as melekhet maḥashevet, “creative activities.”

And this adds an entirely new layer to the difference between the Jewish people’s experience of slavery and their construction of the Mishkan.

As slaves, they performed ‘avodah, their work was drudgery.4 But in building the Mishkan they engaged in melakhah – specifically in melekhet maḥashevet – work that was purposeful and creative.

While the ‘avodah of slavery just required the Jewish people to do things, the Mishkan required their specific creativity and skills – as I explored a couple of weeks ago – as seen by the Torah’s constant mention of the wisdom, understanding, and skill of the Jewish artisans who built the Mishkan (Ex. 28:3; 35:30–35; 36:1–2, 4, 8).

And this meant that the building of the Mishkan rehabilitated the Jewish people from their experience as slaves. By working in a purposeful and creative manner – able to use the skills they possessed – they gleaned a new understanding of what it meant to work. It was no longer shallow and purposeless ‘avodah but deep and meaningful melekhet maḥashevet.

And I’ll add one thing to all of this. Because there is the classic question Pesaḥ raises: all we did was switch from being Pharaoh’s slaves to being God’s slaves – wherein lies the difference?

It’s only by comparing and contrasting the two experiences of ‘avdut, of servitude – Egypt and the Mishkan – that we see the fundamental difference between the two. We were slaves to Pharaoh in Egypt, and all he did was hurt us. But as the servants of the Ribbono Shel Olam, our purpose is to reach the highest spiritual heights and live lives imbued with the deepest possible meaning.

The simple reason it’s called Words of Myrrh is in the tradition of naming Jewish books as puns on the author’s name. My Hebrew name is Mordechai, which Ḥazal (Ḥullin 139b) famously declare to be found in the Torah in a verse we read just a couple of weeks ago in Parashat Ki Tissa: “Where in the Torah can one find a reference to Mordechai? As it is written, ‘you shall take choice spices, five hundred weight of mar dror, myrrh’ (Ex. 30:23).” Would it have made more sense and been more engaging to share this a couple of weeks ago when it was both Purim and the parashah in which the verse is found rather than crowbarring it into a Pesaḥ idea? Probably.

Several people this year asked me for Haggadah recommendations, and I just sent them this.

Nowadays, we only do the first four of the five verses – as the fifth is a reference to having been brought back to the Land of Israel with a Temple in which to worship, which we sadly cannot state at our Sedarim.

Admittedly, ‘avodah can also mean “work that must be done.” In other words, it’s not always meaningless, but it is rarely assumed to be enjoyable. And here I must quote a powerful idea of my rebbi, Rabbi Jeremy Wieder, that tefillah is also called ‘avodah because we must do it regardless, rather than doing it with the expectation of finding meaning.