Wait, U-Netaneh Tokef Lies?!

On the antithetical theology of a central poem

I. The Central Statement

Last week, I focused on the authorship of U-Netaneh Tokef – how, despite the existence of a popular story claiming otherwise, it is a much more ancient poem from 5th- or 6th-century Israel, written by one of Judaism’s legendary poets, Yannai or Ha-Kallir.

This week, however, I want to focus on a different issue with U-Netaneh Tokef, one far more egregious than any false story concerning its origins: How its climax – its central thesis – is a complete inversion of what Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur are truly about.

Let’s begin with the statement itself, one we’re familiar with declaring loudly in shul:

וּתְשׁוּבָה וּתְפִלָּה וּצְדָקָה מַעֲבִירִין אֶת רֽוֹעַ הַגְּזֵרָה

But repentance, prayer, and charity avert the evil of the decree.

Here, there are two issues to address. The first concerns the specific order of these three things that avert the evil of the decree, while the second is U-Netaneh Tokef’s declaration regarding what these three things do: they avert the evil of the decree.

II. The Correct List

In both the Yerushalmi (Ta‘anit 2:1) and Midrash Rabbah (Bereishit 44 §12), R. Elazar is quoted as stating that three things “annul the evil decree” (more on that below): prayer, charity, and repentance.

Noteworthy is the fact that, while it seems clear that the climax of U-Netaneh Tokef is based on R. Elazar’s statement in the Yerushalmi (or midrash), it changes the order of these three things. Where U-Netaneh Tokef placed repentance first in the list, R. Elazar places it last.

Making matters more complicated, still, is a radically different statement in the gemara itself (R.H. 16b). Here, R. Yitzḥak states that four things “tear up a person’s sentence” – with those four being charity, prayer,1 changing one’s name, and changing one’s deeds.

Not only is the order different here – now the list itself is different.

Admittedly, there are some simple ways to reconcile all of these competing lists. Rosh’s version of the gemara, for example, lists only three core ways to tear up the decree: charity, prayer, and changing one’s deeds – changing one’s name, for Rosh, is only listed as what’s termed a “yesh omrim,” a variant opinion within the gemara (Responsa Rosh XVII §12).

Alternatively, the 16th-century Polish Talmudic commentator, Rabbi Shmuel Eidels – better known by his acronym, Maharsha – suggests two additional ways of processing this contrast between R. Yitzḥak’s statement and U-Netaneh Tokef (Ḥiddushei Aggadot, R.H. 16b).

First, changing one’s name (and also changing one’s location, something mentioned in the gemara itself as a yesh omrim to R. Yitzḥak) is simply a matter of changing one’s luck – the person upon whom the decree was uttered is no longer around. Second, he suggests that changing one’s deeds is, ultimately, just a different way of characterizing the process of repentance.

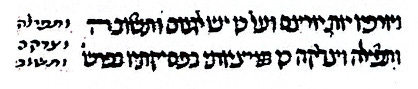

A different way entirely to approach U-Netaneh Tokef’s changing list is to include some indication that it’s wrong. For this reason, there are several maḥzorim from the 16th century that do something to correct the order. While one goes as far as to just simply rewrite it, another writes the letter alef over the word “prayer,” a bet over “charity,” and a gimmel over “repentance” to stress the correct order. A different maḥzor, from the city of Salonika, Greece, from 1522, simply prints the correct order by the side, as can be seen below.

This order problem might also explain the practice of printing the words tzom, “fasting,” over the word “repentance;” kol, “sound,” over the word “prayer;” and mamon, “money,” over the word “charity.” As explained by the 16th-century Galician Rabbi Moshe Mat, the words tzom, kol, and mamon all have the same gematria – the numerical value of the letters all add up to 136 – equating all three, neutralizing any significance to the list’s order.

Taking this idea further, R. Moshe Mat suggests that the order of U-Netaneh Tokef provides the path for true repentance: It starts with a mindset, the need to repent. This mindset leads one to pray, which ultimately leads one to action – giving charity (Maṭeh Moshe §818).

Ultimately, however, what’s clear is that U-Netaneh Tokef’s decision to change its list of three from how the Yerushalmi and Midrash listed them – and, even more so, that U-Netaneh Tokef ignored the gemara’s list of four – bothered many. But here Rabbi Kenneth Brander (in the article I cited last week) offers a much simpler solution to the quandary than anything else.

Ultimately, these tweaks are only a problem if we believe U-Netaneh Tokef was composed in medieval Europe – because they imply that R. Amnon of Mainz consciously ignored the statement of the gemara.

But because we know that U-Netaneh Tokef was written sometime in 5th- or 6th-century Israel, it means that it was composed while the binding nature of the gemara itself was still up for debate – R. Yitzḥak’s view recorded in the gemara would have had a smaller impact upon either Yannai or Ha-Kallir. Indeed, if they were allegiant to anything, it would have been the Yerushalmi also from the Land of Israel.

In other words, rather than rejecting the view of the gemara, U-Netaneh Tokef simply preserves an understanding of the High Holidays from a much earlier time when there was more fluidity to ideas we now see as set in stone.

III. The Radical Rejection of Repentance’s Power

There is a far bigger issue, however, with U-Netaneh Tokef’s claim regarding what repentance, prayer, and charity do: that they avert the evil of the decree.

Because while we can now accept that U-Netaneh Tokef comes from a period of time long before the gemara as we know it gained its power and authority, contrasting U-Netaneh Tokef with the statements of Ḥazal reveals a far more troubling theology.

Both the Yerushalmi and Midrash quoted R. Elazar as saying that prayer, charity, and repentance annul the evil decree – with the word here being mevaṭel. In other words, it’s the belief that, whatever God had decreed for us to suffer in the coming year, it is completely erased by our acts of prayer, charity, and repentance.

Similarly, R. Yitzḥak declared that the four things he believed to have a spiritual impact tear up a person’s decree – using the word kera‘. Indeed, this language is aped in Avinu Malkeinu, in which we ask God, “Our Father, our King,” kera‘, “tear up,” ro‘a gezar, “the evil decree,” dineinu, “against us.”2

In sharp contrast to these statements of Ḥazal, however, U-Netaneh Tokef is far less confident in the power of repentance, prayer, and charity. Because it does not claim that these three things either annul or tear up the decree, it simply states that they ma‘avir, “avert” or “mitigate,” the ro‘a ha-gezeira, “the evilness of the decree.”

The evil decreed against us, U-Netanah Tokef claims, still stands – no matter the extent of our repentance, prayer, and charity. All we can hope for is that the sheer evilness of that decree is ma‘avir, is mitigated. We will still suffer, just hopefully not as much.

Rather than repentance, prayer, and charity representing a possibility for a completely different life, U-Netaneh Tokef declares that they may only slightly tweak a person’s destiny.

This, it’s fair to say, is disquieting – particularly for a poem placed so centrally in our High Holiday prayers. And while part of the explanation might be the same as before – U-Netaneh Tokef dates back to a time when there was much more fluidity concerning the theology of repentance – a deeper understanding of the poem’s inspiration offers a much better explanation, even though it provides no actual comfort from this uncomfortable theme.

IV. The Midrashic Existential Crisis

Though U-Netaneh Tokef is contemporaneous with the latter generations of Ḥazal and clearly, as we’ve seen, departs from their worldview, that doesn’t mean that U-Netaneh Tokef represents a complete rejection of Ḥazal.

In fact, it’s clear that U-Netaneh Tokef draws explicit inspiration from one midrash taken from one of the earliest collections of midrashim in existence – which also dates back to 5th- or 6th-century Israel – the Pesikta de-Rav Kahana (23 §1).

This particular midrash is rooted in the connection between Rosh Hashana and the creation of the world. It begins by stating:

[On the first day of Tishrei] sentence is pronounced upon the countries of the world – who is destined for war and who for peace, who for famine and who for plenty, who for death and who for life. On this day the lives of mortals are scrutinized to determine who is to live and who is to die – for this day was chosen because Adam ha-Rishon was created on Rosh Hashana.

The overlap between this midrash and U-Netaneh Tokef is obvious: “who for war, who for peace, who for famine, etc.” It’s clear that this fueled U-Netaneh Tokef (or, at the very least, it’s clear that whatever inspired the composition of this midrash was the very same thing that inspired U-Netaneh Tokef).

But the midrash goes on to describe in tremendous detail Adam’s first day – noting that within his first day of life (on Rosh Hashana), Adam sinned, was judged, and pardoned. This, the midrash states, led God to declare that the anniversary of this day would forever be humanity’s judgment day.

But here is where things get interesting. Because while the midrash claims that Adam was pardoned, that doesn’t mean he wasn’t still punished – and here, I’m not referring to the Torah’s own description of Adam’s punishment, I’m referring to something different.

Because there is a midrashic trend to believe that, had Adam never sinned, he would’ve lived forever. His ultimate punishment was death – the pardoning he received from God, however, was simply that he did not die instantly. But though Adam was not punished by death immediately, he did still die eventually.

And here, a different midrash underscores another aspect of God’s pardoning of Adam. Though he received a reprieve from instant death, he was now faced with the existential crisis of knowing that one day he would die (Bereishit Rabbah 19 §8).

This is the fundamental fuel of U-Netaneh Tokef. Grappling with the frailness of life, with the many different ways we might die, U-Netaneh Tokef offers a bleak perspective on the limits of what we can achieve during the High Holidays.

Adam was pardoned – but only partially. The evil decree uttered against him, that he would one day die, never went away. All God did on Rosh Hashana was an act of ma‘avir – the harshness of the decree was mitigated: Adam went from facing instant death to uncertain, delayed death.

His evil decree was neither annulled nor torn up – and so, says U-Netaneh Tokef, is the same true for our acts of repentance, prayer, and charity. Because on Rosh Hashana, the anniversary of the day that Adam’s evil decree was mitigated, we can only ever hope for the same.

*

There’s lots more to say and analyze about U-Netaneh Tokef – how it uses the word ma‘avir (or, more accurately, its root, ‘-b-r) seven times throughout the poem to amplify the existential crisis it describes.

But I’ll just note here that it might be wise for us to consider that, rather than leaning into the existential crisis of U-Netaneh Tokef, we might be better placed by recognizing it for what it is and what it is not.

It’s a classic, ancient poem expressing an alternative theology of the High Holidays – one that happened to become included in the maḥzor despite its disagreement with so many other Jewish sources surrounding this time period.

And for that reason, we might consider placing less emphasis upon it, even as we can appreciate where its divergent themes came from.

In truth, R. Yitzḥak uses a different word than prayer here. Instead of using the word tefillah, meaning “prayer,” which is formal and rote – a word that conjures the image of the regular services: Shaḥarit, Minḥa, and Maariv – R. Yitzḥak uses the word tza‘akah, meaning “outcry,” which implies a far more primal, desperate plea to God beyond the obligatory requirements of prayer itself.

This is often misread as kera‘ ro‘a, “tear up the evil,” gezar dineinu, “decreed against us” – which alters the statement’s theology, something Mishnah Berurah takes particular umbrage with (M.B. 622 §10).