Why does the Maḥzor Lie?!

On the false origins of U-Netaneh Tokef

I. The powerful story that never happened

I remember the first time I read the story, told in the ArtScroll Maḥzor, of how the poem U-Netaneh Tokef – one of the most moving and powerful prayers of the High Holidays – came to be composed.

Sometime in the 10th century, the great Rabbi Amnon of Mainz was invited by the Bishop of Mainz to convert, to which he asked for three days to consider the question in order to delay the bishop’s nagging.

Upon returning home, however, R. Amnon realized that he had given the impression that he was genuinely considering conversion. Deeply disturbed by this thought, he spent those three days alone – fasting, weeping, and praying to be forgiven for his sin.

When brought before the bishop at the end of the three days, R. Amnon declined to convert and asked, instead, for the bishop to cut out his tongue for having even implied an interest in converting. But, incensed by R. Amnon’s refusal, the bishop told him that his sin was not with his tongue – it was with his legs, for not running towards the opportunity to convert.

As punishment, the bishop had both of R. Amnon’s feet cut off, joint by joint, before doing the same to his hands. After each and every joint was cut off, R. Amnon was asked if he wanted to convert to Christianity to spare himself more torture, but he refused.

A few days later, on Rosh Hashanah, a mutilated R. Amnon asked to be carried before the Ark just before kedushah at Mussaf, and there he recited U-Netaneh Tokef for the first time, passing away mere moments after. Three days later, R. Amnon appeared in a dream to another Mainzer rabbi and taught him the prayer, still recited to this day – the centerpiece of the High Holiday service.

II. Rabbi João of Newcastle

ArtScroll were not the first to tell this story – it is first recorded by the 13th-century Rabbi Yitzḥak b. Moshe of Vienna, in his influential halakhic work entitled Ohr Zaru‘a (Vol. II §276 [Laws of Rosh Hashanah]), in which he reports having read the story in a work by Rabbi Ephraim of Bonn, a 12th-century rabbi best known for recording various episodes of medieval Jewish persecution.

But this is where the problems begin.

For starters, despite the Ohr Zaru‘a describing R. Amnon of Mainz as “the leader of the generation, wealthy and good-looking,” no other record exists testifying to his existence – which is strange given how religiously important he was, per the Ohr Zaru‘a.

This is made all the more confusing by his name, Amnon. Because, while we don’t pick up on this, it’s a name more fitting for an Italian Jew, not a German-Jewish one.1 The idea of a deeply influential German rabbi bearing the name “Amnon” would be surprising. It’s a bit like reading a story set in Medieval England, where the main character was called João.

All of which is only amplified by the way Ohr Zaru‘a offers a homiletic explanation for his name – that he was called R. Amnon (אמנון), “because he believed (he’emin, האמין), in the Living God and suffered harsh afflictions for his faith (emunato, אמונתו).” R. Amnon’s name bearing such a striking similarity to the theme of the story only adds another layer of suspect artificiality.

But the issues with U-Netaneh Tokef are not limited solely to the questions surrounding its author’s name. Experts in German medieval poetry – a group of people I am neither a part of nor do I have much desire to meet at parties – argue that there is little in U-Netaneh Tokef to suggest that it is from that era. Indeed, it bears a far more striking similarity to the poetry of the legendary 5th- and 6th-century Jewish poets, Yannai and Eliezer Ha-Kallir. Indeed, while R. Ephraim of Bonn is best-known for recording Jewish persecution, his other claim to fame was his knowledge of Yannai and Ha-Kallir.

Now, all of these issues might seem a tad persnickety. Because you could suggest answers to them all. It’s not impossible that there was an otherwise unknown famous rabbi in Mainz – we don’t know the names of every major rabbi in Europe. And it’s neither impossible that he was from an Italian family that moved to Germany, nor that he was given a name that would later come to define his faith.

Nominative determinism, the belief that people’s names come to define them, is a well-attested phenomenon, after all. Not only was the legendary manager of Arsenal called Arsene Wenger, but – in a fact I know many of you are more likely to share around your Shabbat table than any of the Torah I write – from 1998–2003, VfL Wolfsburg, a German soccer club, were managed by Wolfgang Wolf.

And who’s to say that R. Amnon of Mainz wasn’t a good enough poet to write a more classically styled poem?

Nonetheless, there’s a final issue with the story that is truly the nail in the coffin.

III. The undeniable evidence

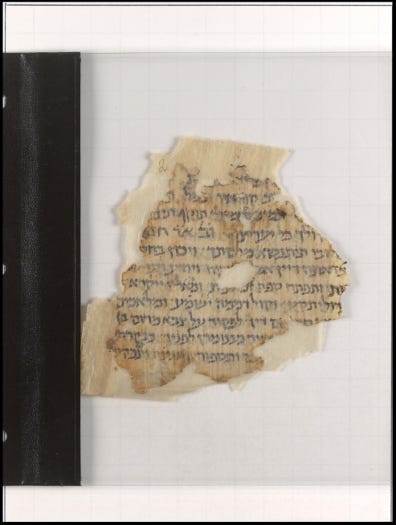

What you’re looking at is not just, as MSWord suggested captioning it, “a piece of paper with written text upon it,” but a piece of parchment with the written text of U-Netaneh Tokef upon it from the Cairo Genizah that you can view here. Not only does this place the location of U-Netaneh Tokef far from Germany, but also, due to the magic of how Cairo Genizah manuscripts can be analyzed, it indisputably dates U-Netaneh Tokef to a much earlier period: 6th-century Israel. Four hundred years earlier than – and thousands of miles from – the story of R. Amnon of Mainz.

IV. The depressing explanation

Given that R. Amnon of Mainz – if he ever even existed – is most certainly not the author of U-Netaneh Tokef, how did such a popular legend emerge? Why did the Or Zaru‘a claim such an origin story?

In his treatment of U-Netaneh Tokef, Rabbi Dr. Kenneth Brander offers a fascinating suggestion.2 It starts with the observation that U-Netaneh Tokef only became part of the High Holiday service in the era following the Crusades.

Until then, U-Netaneh Tokef would have been of little renown – known only to figures such as R. Ephraim of Bonn, who were experts in Yannai and Ha-Kallir. But, as R. Brander points out, following the crusades, U-Netaneh Tokef would have been far more relevant to the Jewish communities in Medieval Europe.

The poem’s focus, after all, is on death – the idea that Jews are not just being judged on whether they will live or die, but through which particularly horrific manner they will die. Will it be the sword? Famine? Fire? Wild beast? Strangulation? Plague? Drowning? There is an almost dark humor to U-Netaneh Tokef’s grasp of the multiple ways a person might die in the medieval era, particularly at the hands of crusaders.

It’s no surprise, then, that a story would develop to add another connective layer between the experience of Jews during the Crusades and U-Netaneh Tokef. Rather than being an ancient poem by Yannai or Ha-Kallir, U-Netaneh Tokef became a poem written for the Crusades by the Crusades. In doing so, its meaning was amplified further.

For us, however, such a misattribution no longer holds sway. Instead, it’d be better if we appreciated U-Netaneh Tokef for what it actually is and when it was actually written. And, as we’ll see next week, such a recognition helps explain one of the poem’s most Qontroversial lines.

I don’t know if this is the logic behind why the kosher frozen pizza brand is called Amnon’s Pizza, but if it is, it’s genius.

“U-Netaneh Tokef: Will the Real Author Please Stand Up” Mitokh Ha-Ohel: The Festival Prayers (2017, Maggid Books) 75–86.